Any writer trying to tackle the art of composing a children’s story will agree—it’s tough work. Whether writing a 500-word picture book or a 75,000-word novel, writers face a juggling act of theme (without being didactic), character (without being overly cutesy), story (with the perfect pace), and more all in effort to create that sweet balance of delight, entertainment, meaning, and connection. But what makes a story good? In Celebrating Children's Books: Essays on Children's Literature, Arnold Lobel says, “A good picture book should be true. That is to say, it should rise out of the lives and passions of its creators.” Perhaps this statement could be pushed a step further, so it reads: A good children’s book (picture book through young adult novel) should be true. That is to say it should rise out of the lives and passions of its creators and have a placeholder for a child to insert themselves and their emotions. A good book should have heart.

In author Kate DiCamillo’s 2014 Newbery speech, she

said, “…[those] working on stories, bookmaking, and art are given the sacred

task of making hearts larger through story.” But what is heart and how does an

author write it into a story? To figure this out, I asked three experts for

their thoughts on heart in children’s books: Author Beth Anderson, Senior Editor

at Chronicle Books, Melissa Manlove, and Senior Editor at HarperCollins, Maria

Barbo.

First meet Beth. Not only is Beth Anderson the author

of several picture books, she also writes about emotional resonance in her blog, “Mining for Heart.” Beth says, “Heart” is the

treasure I’m after whenever I start a new manuscript. What will make this story

more than a reporting of events? What will make the child reader think about

the world a little bit differently? What will bring emotional resonance? To me,

heart is not the theme or focus nugget but is much deeper and more personal. It

emerges when you process the research or story through your own life

experiences and passions to find a unique angle or thread. “Heart” can be

nebulous, elusive, downright torture to tackle, but it’s what makes a

manuscript sing!”

Beth’s

statement screams many truths, (the torture!). She also wonders, “What will

make a child reader think about the world a bit differently?” Kimberly Reynolds,

author of Children’s Literature: A Very Short Introduction, says, “Because

children’s literature is one of the earliest ways in which the young encounter

stories, it plays a powerful role in shaping how we think about and understand

the world.” Reynolds’ statement echoes Kate DiCamillo. In essence, they are

both saying that books play a powerful role that might affect the way children

understand and think about race, religion, ableism, neurodiversity, gender

identity and more. No wonder DiCamillo calls it a “sacred” task.

Helping a child think about the world a bit

differently happens when an author succeeds at writing a story that gets under their skin. There, inside the pulse of the story is the opportunity for a child or young adult

to connect, beyond mere amusement, so that the story seeps

into their pores and stays long after the last page is read. To

jump-start a pulse that pushes a story beyond entertaining-but-forgettable, a book

must have 💙heart💙, and to achieve heart the writer must make the reader feel

something.

The

Horn Book Magazine also covers the need for children’s stories to

have heart and feeling-points. In a November 2012 article

titled “Making Picture Books: The Words” by Charlotte Zolotow, Zolotow

emphasizes how an emotional impulse to write for children should come out of a

real place and says, “Many fine writers can write about children but are unable

to write for them.” She says, “The

writers writing about children are looking back. The writers writing for

children are feeling back into childhood.” It is the feeling-points that

writers must tap into if they want to reach a child’s heart.

The next step in my mission to understand heart took me to Senior Editor Melissa Manlove from Chronicle Books. I knew Melissa would be the perfect person to talk to, because she made me work to uncover the heart of The Elephants Come Home (Chronicle Books, 2021). Back in 2012, I approached Melissa with a true story about a man named Lawrence Anthony who rescued a herd of seven elephants in Zululand, South Africa--the elephants had broken out of every other wildlife sanctuary they'd lived at and had thus frightened many townfolk with their destruction. Now they had to be relocated again, otherwise they would be shot! Melissa and I were both captivated by the many details of this story, but something was missing—that nebulous “something” was the heart. It sat in the outskirts of my writing, but the heart was too buried to actually feel it. I had to work, to dig, to revise until I was able to identify the true piece of me that I was bringing to the story (for me, it was growing up as a military brat and being made to move from home to home, like the elephants). Once I identified the heart I felt when I thought about this story, I knew I couldn’t shove it front and center because then the story would feel forced. Melissa says heart can’t be in the reader’s face. It needs to be like a treasure chest the reader works to uncover.

Actually, she says it more eloquently. Melissa says, “The writers I admire most tend to be ones that, as they draft, are following a feeling, a hunch, a question. They’re feeling out what seems right and what the story seems to want to be. And THEN from that, later, in the revision process, they figure out what that part of us that lives on story but doesn’t have words of its own to speak was trying to say. And when you let the story come first, and let it show you by feel where the heart is, then the heart is truly buried in it, like buried treasure, and your story becomes a map for those who will follow you.”

The

Elephants Come Home written by me and with gorgeous illustrations by Hadley Hooper, released in 2021 with Chronicle Books. Melissa pushed me to dig deep so that I

could leave a treasure for readers to find.

Melissa is a master of theme and thesis and if you ever

have the opportunity to attend one of her lectures, it will be the best gift

you ever give yourself. For this article, I asked Melissa to expand on feeling

points, and she explained that, “Many [stories are] disposable. And that’s

because they’re entertaining in the moment, but they don’t mean anything. There’s

nothing that stays with you afterward, nothing that nibbles at your imagination

and pulls you back to them.” Even if a story is fiction, Melissa says a good

story makes us “feel it is true.” Melissa explains that feeling in story

is “the language-brain articulating what the story-brain had already known in feeling.

A storyteller must evoke a universal feeling.” Melissa says for a story to go

deeper, there needs to be “a human experience at the heart of that story that

we all can relate to…and a truth about that human experience in the story.”

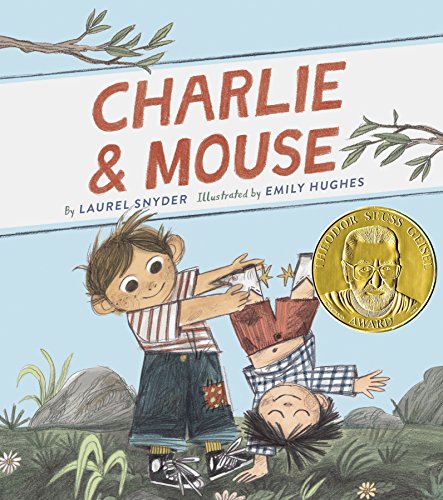

A great example of a human experience at the heart of

a story we can relate to is Charlie and Mouse, edited by Melissa Manlove,

written by Laurel Snyder, and illustrated by Emily Hughes. The starred

review written by Elizabeth Bird in School Library Journal starts out with a

negative tone, “Only the

jaded should write reviews of children’s books.” The reviewer goes

on to say, “If I am a parent and

there is any danger AT ALL that my child is going to ask me to read and reread

and reread again a piece of tripe that calls itself a children’s book, I at

least want some forewarning. I have great love for the sardonic stripe of

reviewer. Anyone who has honed their teeth on the literary darlings of

sweetness & light.” Elizabeth Bird says she is sick and tired of reading

overly-sweet books and goes on to add, “So I sometimes wonder if having my own

kids has made me more inclined towards books with a glint of true emotion

amidst the adorableness. With that in mind, I guess I could be forgiven for

initially thinking that Charlie & Mouse wouldn’t work for me. Heck the eyeballs of these kids

take up half their heads as it is. Yet when I read this story what I found was

a quietly subversive, infinitely charming, eerily rereadable early chapter book

not just worth reading but worth owning.” Though Bird set out to dislike

Charlie and Mouse, she felt the heart and says, “my tolerance for the

cutesy is distinctly low. So it was with great pleasure that I discovered that

while the characters of Charlie and Mouse are undeniably cute, they are not

cloying. They are not vying for your love. They are living their lives, doing

what they want to do, and if what they do happens to be cute, so be it, but

that is not their prerogative.” Heart won the day.

A great example of a human experience at the heart of

a story we can relate to is Charlie and Mouse, edited by Melissa Manlove,

written by Laurel Snyder, and illustrated by Emily Hughes. The starred

review written by Elizabeth Bird in School Library Journal starts out with a

negative tone, “Only the

jaded should write reviews of children’s books.” The reviewer goes

on to say, “If I am a parent and

there is any danger AT ALL that my child is going to ask me to read and reread

and reread again a piece of tripe that calls itself a children’s book, I at

least want some forewarning. I have great love for the sardonic stripe of

reviewer. Anyone who has honed their teeth on the literary darlings of

sweetness & light.” Elizabeth Bird says she is sick and tired of reading

overly-sweet books and goes on to add, “So I sometimes wonder if having my own

kids has made me more inclined towards books with a glint of true emotion

amidst the adorableness. With that in mind, I guess I could be forgiven for

initially thinking that Charlie & Mouse wouldn’t work for me. Heck the eyeballs of these kids

take up half their heads as it is. Yet when I read this story what I found was

a quietly subversive, infinitely charming, eerily rereadable early chapter book

not just worth reading but worth owning.” Though Bird set out to dislike

Charlie and Mouse, she felt the heart and says, “my tolerance for the

cutesy is distinctly low. So it was with great pleasure that I discovered that

while the characters of Charlie and Mouse are undeniably cute, they are not

cloying. They are not vying for your love. They are living their lives, doing

what they want to do, and if what they do happens to be cute, so be it, but

that is not their prerogative.” Heart won the day.

I

circle back to Kate DiCamillo, because Flora and Ulysses is

a great example of a book with heart, and it was a very human and universal

experience that led DiCamillo to write this Newbery Award winning book—the

experience of love, grief, and loss. DiCamillo says her truth rose out of her

deep love for her mother who often asked who would take care of her Electrolux

vacuum cleaner when she passed away. In January 2009, her 86-year-old mother

fell, broke her hip, and died less than a week later. DiCamillo’s heart ached,

and she grieved as painfully and deeply as anyone who loses a loved one

grieves. In her 2014 Newbery speech, she says she wrote Flora and Ulysses because

she “wanted to excavate that grief.” She says, “I wanted and needed to find my

way to joy.” This was her truth, but she doesn’t lay it on the page so

literally. The truth takes on new forms and shows up in her book through

characters that would have made her mother laugh—Flora, the squirrel, the giant

donut, and a vacuum cleaner (remember the Electrolux), and it’s not just any

vacuum cleaner, but one that gives the squirrel superpowers!

The Newbery committee called Flora and Ulysses

a story of hope, joy, and love. Through this book, readers experience real

feelings filtered through DiCamillo’s characters while originating from her

authentic human experience—her love and grief and also her hope to regain

laughter and joy. This echoes back to what Melissa Manlove said, “there needs

to be “a human experience at the heart of story that we all can

relate to…and a truth about that human experience in the story.” In the

end of Flora and Ulysses, readers discover that Flora’s father, George

Buckman, has a capacious heart. One that is very large and “capable of

containing much joy and much sorrow.” And this is parallel to the truth of

DiCamillo’s heart, joy, and sorrow in her mourning process. Authentic feelings

that showed up on the pages.

The Newbery committee called Flora and Ulysses

a story of hope, joy, and love. Through this book, readers experience real

feelings filtered through DiCamillo’s characters while originating from her

authentic human experience—her love and grief and also her hope to regain

laughter and joy. This echoes back to what Melissa Manlove said, “there needs

to be “a human experience at the heart of story that we all can

relate to…and a truth about that human experience in the story.” In the

end of Flora and Ulysses, readers discover that Flora’s father, George

Buckman, has a capacious heart. One that is very large and “capable of

containing much joy and much sorrow.” And this is parallel to the truth of

DiCamillo’s heart, joy, and sorrow in her mourning process. Authentic feelings

that showed up on the pages.Senior Editor Maria Barbo from HarperCollins says, “Authenticity is key for emotional resonance. That thing you do in private that you think nobody else does—someone does it. A writer or artist has to make themselves vulnerable in that way—to share the secret, raw parts of themselves because relatability stems, in part, from specificity.” She adds a reminder, “The reader’s heart isn’t going to be in it if yours isn’t.” Maria is the editor for Bubbles...Up! a love poem to swimming, written by Jacqueline Davies illustrated by Sonia Sánchez. Each reader might find a different pulse point as they read, but without a doubt this story has heart.💙

The experts agree—a good book should

have heart. Melissa Manlove says, a “good story must feel true.” Maria

Barbo says that a reader’s heart can’t be in it unless the writer’s heart shows

up first. Beth Anderson challenges authors to

find what will cause the child reader to think about their world view. Children’s

Literature: A Very Short Introduction says, “Children’s literature

can also be a literature of contestation, offering alternative views and

providing the kind of information and approaches that can inspire new ways of

thinking about the world and how it could be shaped in other, potentially

better ways.” Heart shows up when we process stories through life and

literature experiences. Writers all have something that is deeply

personal to share. We have something that, as Arnold Lobel says, “…can rise out

of [our] lives and passions.” The real question is: are we willing to be

vulnerable and write from an authentic place and share our feeling-points so

the story can come alive for a child.

At the end of Kate DiCamillo’s Newbery speech, she said that as a child, she sat with books in her tree-house and could, “Feel the stories I read pushing against the walls of my heart.” For her, those stories traveled beyond the boundaries of mere entertainment and had a lasting pulse. Again, DiCamillo says those, “…working on stories, bookmaking, and art are given the sacred task of making hearts larger through story.” Writers can only do this if they dig deep and give of themselves so authentically that a book develops a pulse—a story that not only entertains but also has a placeholder for the child to insert themselves and their emotions. Children deserve stories that have heart.