Fast

Five with Editor Emma Ledbetter

Emma

Ledbetter is an associate editor at Atheneum Books for Young

Readers. She is also on the faculty for the Rocky

Mountain Chapter of the SCBWI fall conference scheduled September 19-20, 2015.

Registration can be found here: Follow this link or type in:

https://rmc.scbwi.org

Hi, Emma.

Thank you for serving

on the faculty for the upcoming RMC SCBWI fall conference, and for agreeing to

this interview. I want to let our participants feel like they know you even

before your plane lands at Denver International Airport, so again, thank you

for taking the time to answer the following questions:

Here’s the bio info I

hijacked off of Atheneum’s website:

Emma Ledbetter, Associate Editor

Emma Ledbetter, Associate Editor

Emma joined Simon and Schuster in 2011 following

internships at Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, Nickelodeon, and Nick Jr.

She graduated from Yale University with a B.A. in Art History, where she wrote

her thesis on the art of Little Golden Books and (re)discovered her passion for

children's literature. Books that Emma has edited include

The Backwards

Birthday Party, a picture book by singer/songwriter Tom Chapin

and John Forster and illustrated by Chuck Groenink,

and I Don't Like

Koala, a hilarious picture book-noir from Sean Ferrell

and Charles Santoso. She continues to look for captivating voices,

enchanting artwork, humor, and charm in a range of formats—particularly picture books, chapter books, and

middle grade novels. She is especially fond of Edward Gorey, Clementine, and

Frances the Badger.

|

| The Backwards Birthday Party by Tom Chapinand John Forster. Illustrated by Chuck Groenink |

ICE BREAKER: You

attended Yale, wow! And you have impressive internships under your belt, too,

not to mention the fun titles you’ve edited (here’s another to add to the list

above,

What About Moose by Corey Rosen

Schwartz and Rebecca J. Gomez Illustrated by Keika Yamaguchi). Now that I’m in

awe of you, please tell me something to make me feel like your BFF. Something

only the insiders in your life know:

Thanks

Kim, you’re very kind! I love ice cream and frozen yogurt, and my preferences

tend toward those of a small child: eg. chocolate with sour patch kids (gross,

I know), and strawberry with rainbow sprinkles.

Nice, sounds like my kind of breakfast (we are talking breakfast foods, right?).

1. In your 2014 interview with the MD/SE

region of the SCBWI, you said you have a particular love for “picture books of

all stripes”. That’s awesome news for our picture book authors. I’d love to

hear more. Please provide depth about what captivates you.

Also,

does “all stripes” include fiction and nonfiction? Rhyming? Concept books?

I really do love it all when it comes to picture books: stripes,

solids, and polka dots. A manuscript or dummy doesn’t have to fall into a

particular category to captivate me; I’m looking for things like stellar

writing and originality. I want that heart-melty feeling you get when you read

something totally fresh and clever, beautifully written and/or illustrated; these

qualities can come from all sorts of places. Here are three differently striped

examples from my list:

1. What About Moose,

which you mention above, is a picture book in rhyme. I bought it because I love

the character of Moose, I love the non-didactic, witty message about teamwork,

and I’m captivated by the verse, which is lively and fun, uses unexpected

rhymes, and reads completely naturally. I’m very sensitive to clunky meter—which

never does a story any favors—but

Corey and Rebecca’s flows perfectly.

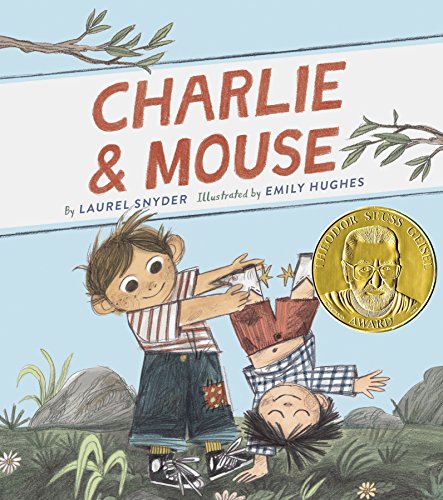

2. A really special book I have coming out this spring is called

Ida, Always, written by Caron Levis

and illustrated by

Charles Santoso. It’s a fictional story about two polar bears from the Central

Park Zoo: Gus learns about grief when his friend Ida becomes very sick and dies.

It’s quite a tough subject, but the writing is absolutely stunning (as are the

illustrations!). This book captivates me because its story is really needed, and importantly, because Caron’s

approach is just right—gentle and appropriate and honest.

3. In the nonfiction realm, I recently bought a picture book

biography about illustrator and Disney concept artist Mary Blair: Pocket Full of Colors by Amy Guglielmo

and Jacqueline Tourville, to be illustrated by Brigette Barrager. The

manuscript captivated me because a) Mary Blair is a little-known figure who led

a fascinating life, and b) Amy and Jacqueline use a clever framework to tell her

story—it’s all about color and imagination, and being a girl in a boy’s world,

and it’s written with a creative young audience in mind; at no point does it

feel like a dull info-dump. (It didn’t hurt that I studied Mary Blair in

college and am actually quite obsessed with her, but Amy and Jacqueline didn’t

know that when they submitted their project to me!)

(Please excuse this brief pause in the interview as I run to Boulder Bookstore to purchase a copy of What About Moose right now!)

2.

To Note or not to Note, This is the

Question. I often hear a lot of

conflicting chatter centered on making illustration notes. I understand the

writer should not dictate to the illustrator about what a character looks like

or how to lay out a scene, but sometimes jokes in the writer’s mind are held

not in the text but in the illustration (i.e. the text may say, “Mommy loves it

when I help” but the illustrations must show the exact opposite in order for

the joke to work). How do you feel about the use of illustration notes (art

notes) and how do you suggest a writer handle making these notes?

Yes, this is a tough question. If you see the illustrations as

portraying the opposite of what the text says, yep, that’s important, not only

to the illustrator when s/he comes on board, but also to the heart of your

story, and to my understanding of it as I consider your manuscript. So if you

write “Mommy loves it when I help,” but you don’t want that to be interpreted

literally, you should absolutely include something like: “Art note: Bob is

actually doing the exact opposite of helping.” What you should NOT write is

“Art note: while Mommy is mixing cake batter in the background, Bob is crawling

on the counter, with one hand in the sprinkles, and the other hand smearing

pink icing all over the wall.” The first gives us crucial information about the

story’s intention and the nature of Bob as a character; the second is

encroaching on the illustrator’s freedom to interpret your text.

If you do have that specific of a vision, and there’s a good (GOOD)

reason behind it—say, it’s important to the plot that Mommy and Bob make a cake,

or even that its icing has to be pink—go ahead and write that. Just think

carefully about your reasoning behind each note, and don’t go overboard. Since

I’m being totally honest here, if I don’t see certain art notes as strictly

necessary, sometimes I just delete them before sending a manuscript to an illustrator

to consider. Most artists won’t want to take on a project that doesn’t leave

them room to breathe and be creative. Picture books are the ultimate team

effort!

3.

Please tell me about the list you’re

currently building—what you’ve recently acquired, for what publication year,

and how you plan to shape that list (pb, er, mg, ya/fiction or nonfiction),

including how many books you acquire per year.

See #1 for some examples of what I have coming up. I have a few

awesome books trickling out in 2016 (starting with Ida, Always), and my list kicks into gear in 2017, where I

currently have 17 books scheduled to publish—mostly picture books, a couple

chapter books and a couple middle grades. I’m aiming to have about 10-15 books publish

a year (whoops, sorry 2017!) and continue to be most interested in acquiring middle

grade novels and picture books.

4.

How much importance do you place on

authors needing a social media platform, and if you consider a platform

extremely important, which forms of social media do you recommend?

Also,

I’m scratching my head over your Twitter handle @brdnjamforemma in longspeak,

is that “Board and jam for Emma,” or “Bird ‘n jam for Emma” or am I not even

close?

I don’t see it as a do-or-die

scenario—you should do what you’re comfortable with and natural at—but being an

active and creative self-promoter is a definite plus once your book is on the

path to publication, because it can really help get the word out.

And I’m glad you asked that! It’s

“Bread and Jam for Emma,” a play on Bread

and Jam for Frances, which is one of my all-time favorite picture books. #picturebooknerd!

And I’m glad you asked that! It’s

“Bread and Jam for Emma,” a play on Bread

and Jam for Frances, which is one of my all-time favorite picture books. #picturebooknerd!

(Ugh! I can't believe I didn't figure that out. I LOVED that book when I was little. I still have my tattered copy!)

5.

I recently attended the SCBWI

International conference in California where Wendy Loggia peppered a panel of editors

with a series of questions. I’m asking you and all members of our RMC faculty

to pretend you’re on that California panel, too—picture Los Angeles, the sun warms

your face, and you’re about to dash out to the pool bar and order something

exotic, but first you must dazzle the audience with answers to the following

questions:

a. What hooks you in a manuscript?

Creativity and originality;

something I’ve never seen before. Manuscripts that are surprising, exciting,

touching, hilarious, charming, sly, weird. (Maybe not all those things at once, but kudos to you if you pull that off).

b. What

turns you off when reading a manuscript?

I’ll give a picture

book-specific answer: manuscripts that feel formulaic; manuscripts that make me

suspect the author hasn’t actually read very many picture books (I can tell);

manuscripts that haven’t given any thought to the visual opportunities (eg. an

entire story that takes place in one room between two characters will not usually

lend itself to good page turns and variety in the illustrations).

I’m also pretty sick of picture

book manuscripts that are written as lists, eg. “Eight Easy Ways to Annoy Your Little Brother!” Books of this nature can be very clever, certainly—but they

often seem to be formatted this way as an excuse to avoid getting into the good

stuff, like character and plot, and therefore they have become a personal pet

peeve.

c. What’s

on your #MSWL (for those of you on Twitter, #MSWL is where agents and editors

post their Manuscript Wish List)?

I’m not so into the #MSWL.

On mine are books I don’t even think to want, and then desperately want when

they appear in my inbox. These include a picture book about firefighting ducks;

a practically-wordless book about a grandmother who uses elaborate methods to

deliver a box of cookies to her grandson; a lyrical and thoughtful picture book

about all the different parts of a house and where each came from, once; and

one about honeybees written in gorgeous, buzzy verse. (I already have these,

though; they’ll all be out in 2017).

Can I please have a strawberry

daiquiri?

You deserve one (with rainbow sprinkles). Thank you so much for your time!

.jpg?_&d2lSessionVal=IYGXRRcTDaKhdXrZkN1JUfusY)