Top Ten Tricks to Revise your Writing and Make your Manuscript Sing©

By Kim Tomsic

I recently met with a group of children’s book

writers for a brain-storming session on revision techniques. Here’s what we

came up with:

1. Choose strong verbs

to make your sentences active NOT passive.

.JPG) 2.

Use consonants to nail humor. Comedy writers say consonants are

funnier than vowels, so revise word choice where needed. For example, corndog is funnier

than ice cream, upchuck is funnier than vomit.

2.

Use consonants to nail humor. Comedy writers say consonants are

funnier than vowels, so revise word choice where needed. For example, corndog is funnier

than ice cream, upchuck is funnier than vomit.

3. Watch out for using “STARTS”. Avoid having your character “start” or “begin” something.

Don’t have him start walking down the street or begin making dinner. Think like

Nike™—just do it! The exception: “Started”

works when the character begins to do something, but then stops, i.e. “I started to close the door, but the

stranger caught it with his foot.”

4.

Showing makes us feel closer to the protagonist. Duh! As writers, we’ve heard this a gazillion

times—show don’t tell. And sure, there are moments to tell, but if you want your reader walking shoulder-to-

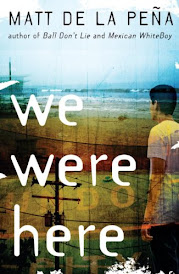

shoulder with your protagonist, showing is a smart way to put the reader in the protagonist's shoes. We all know that, yet we still make the mistake of too much telling. Not to worry, that’s what revisions are for! When editing your manuscript, weigh every sentence in your story. Does it show or does it tell? I have an amazing example borrowed from Matt de la Peña’s book, We Were Here. In the book, the main character is smack in the middle of a first kiss. Instead of giving the reader a “tell” line like, “I was nervous” or “I felt awkward” the author shows how the character felt by writing:

shoulder with your protagonist, showing is a smart way to put the reader in the protagonist's shoes. We all know that, yet we still make the mistake of too much telling. Not to worry, that’s what revisions are for! When editing your manuscript, weigh every sentence in your story. Does it show or does it tell? I have an amazing example borrowed from Matt de la Peña’s book, We Were Here. In the book, the main character is smack in the middle of a first kiss. Instead of giving the reader a “tell” line like, “I was nervous” or “I felt awkward” the author shows how the character felt by writing:

On the outside I tried to make like everything was super smooth and calm and my palms were dry as hell, but inside my mind was thinking all kinds of crazy thoughts like: How long do I keep my mouth open? And when do I turn my face? And how much tongue do I use? And where do I put my hands? And how are we supposed to breathe?(255).

5.

Listen to the voice. Ask yourself if each line meets the

voice you intend to convey. Read it aloud and think of your audience. If you

get bored with the sound of your prose, your audience will grow bored, too. Next,

have somebody else read your story aloud and listen to the words with fresh

ears (especially picture book writers). You may hear the reader emphasize words

you did not intend to highlight, or you may hear the story exactly as you

anticipated.

6.

DO

THE EXTRA WORK. If you know your writing weaknesses,

search your manuscript for those problem areas. Read books in your genre. Use

tools—author John

McPhee advises writers to skip the thesaurus and use the

dictionary when looking for better words. He says the dictionary gives the subtle

nuances around the meaning of words and can inspire better choices. I say use both!

7.

Keep

a rules book, especially if your story has magic. And

let your readers in on the rules, so they

understand the stakes. Also make a timeline for your story to keep things in sync. I remember one author saying his copy editor found he had eight weeks in his October!

understand the stakes. Also make a timeline for your story to keep things in sync. I remember one author saying his copy editor found he had eight weeks in his October!

8.

Make

a check list to see if your story contains

satisfying plot elements.

¨ Does your character have a want (and does reader want to root for MC)?

¨ Do you have a flawed protagonist? I hope so! Nobody wants to root for a perfect character.

¨ Is there an inciting incident?

¨ Does your story have real stakes and tension?

¨ Does your main character (m.c.) make things

happen, instead of having a bunch of things happen to him?

¨ Do you have a compelling antagonist vs. a

gratuitous antagonist?

¨ Do you have interesting subplots?

¨ Does your protagonist make a big decisions that

propels them through a couple of “doorways” ? A doorway, in my eyes, is a point

of no return—imagine toothpaste squeezing out of a tube, once you squeeze it

out, you can’t put it back in. Some giant examples include: killing someone,

announcing a classmate's secret over the school’s loudspeakers, burning down a

building…those are all things you can’t undo…you can’t unkill (in most books),

you can’t untell, you can’t unburn. **Please note—the doorways are the most compelling when your

main character makes a decision, NOT when something happens to them. However, sometimes a protagonist is thrust into Act II. But from that point forward, make sure they drive the plot movement.

¨ Do you have "But" or "Therefore" action between story beats (you should!) rather than "and then this happens...and then this happens." Want to know more? Check out this video at NYU with the makers of South Park.

¨ Do

you have a second doorway that leads into Act III? I hope so!

¨ Do you have a black moment when your main

character almost gives up or feels at his low?

¨ Do you have a showdown moment and/or a climax?

¨ Does your main character change by the end of

the story?

¨ Did you tie up loose ends?

9.

JOIN A CRITIQUING GROUP. Get involved in a critiquing group and listen to

at least some of the advice. Be a good receiver and a good reviewer. We get so

close to our work, it's hard to hear it clearly after a while. The more you

critique somebody's work, the more you're able to see the flaws that need

fixing in your own manuscript.

WORKING WITH ME: I'd love to speak at your workshop, conference, or school! Contact me here.

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment